The real estate sector is often perceived as sluggish and resistant to technological advancements. However, lots of big-name firms have been taking innovation seriously over the last decade. These firms deserve a lot of credit.

Many of these firms would admit that the returns on this innovation have been underwhelming. This is not necessarily a failure, because trying new things brings about uncertainty, and hopefully leads to insights useful for the future.

It would be unfortunate if the dearth of home runs prevents these investors from continuing to take swings. For this piece, I want to step back and explore the concept of “disruption”, and whether we might be missing a little something as an industry.

What is “Disruption”?

When we think about “innovation” and “disruption” in real estate, what immediately comes to mind? Maybe a fancy building management software app, a Virtual Reality tool, a shiny LEED building, or something else that is new, neat and expensive.

30 years ago, Clayton Christensen wrote ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’, in which he considered how well-equipped, successful companies with skilled management frequently succumbed to competitors offering simpler and seemingly inferior products. His theory of disruptive innovation unravels this intriguing process.

Types of Disruptions

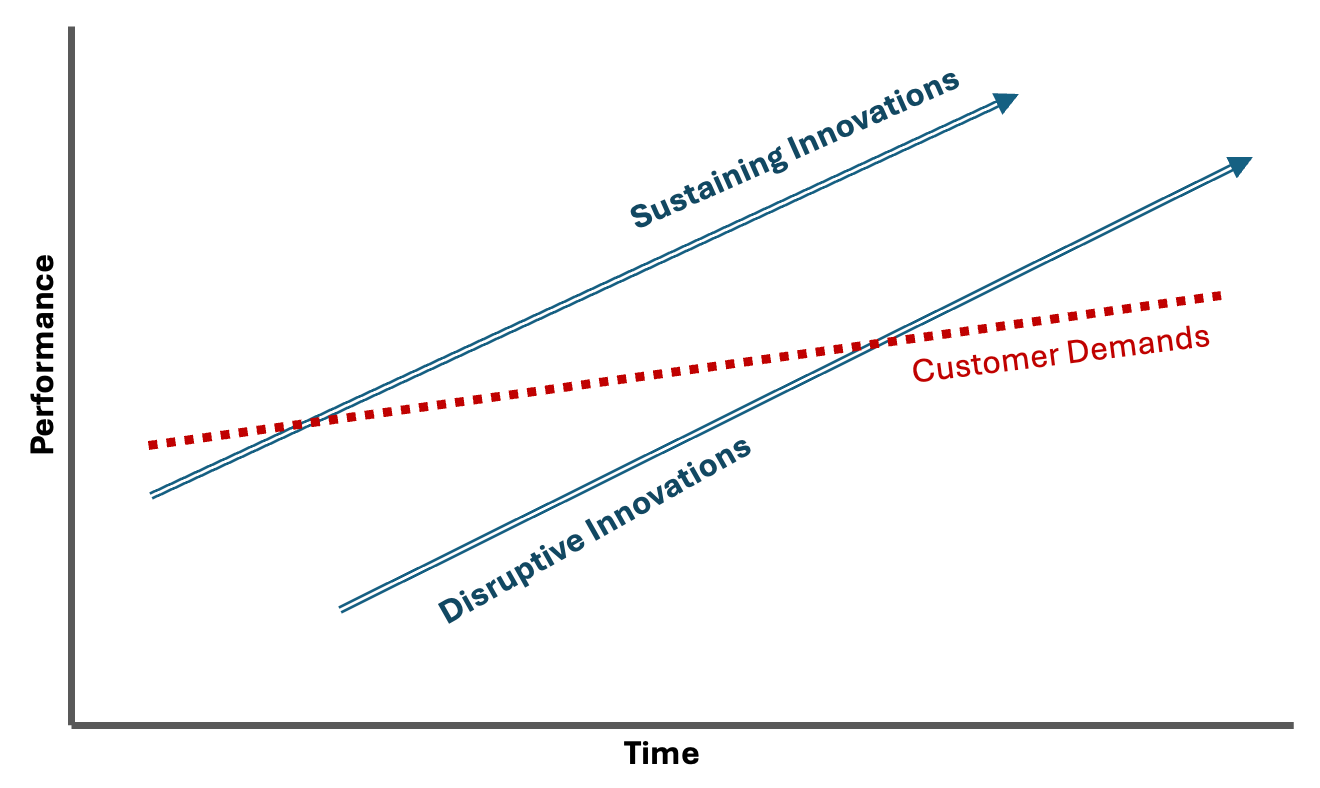

Christensen begins by distinguishing between sustaining and disruptive innovations. Sustaining innovations foster existing product improvement. Successful firms making their current products a bit better through time. Disruptive innovations come from new entrepreneurs, attacking the same market, in a different way.

The graph below presents this model visually. The middle line represents the range of current customer needs, which gently slopes upward through time. The upper line illustrates the path of sustaining innovations, which exceed customer expectations. Below it, a parallel line shows the trajectory of disruptive innovations.

These disruptive innovations initially attract a niche market with benefits like lower costs, compact design, or improved convenience. While they may underperform in the existing market initially, they adequately serve a specific customer segment.

One key insight of this model is that innovations often improve at a faster rate than the market demands. Established companies, through sustaining innovations, overshoot the market and provide more than the market needs.

Overshooting the Market

Christensen’s research shows that incumbents utilize sustaining innovation to seek out higher margins and flashier products and customers. In so doing they often “overshoot the market”, offering customers more than they currently want or need. This desire to continually further differentiate is logical, but often counterproductive, as the pool of demand thins out as the curve steepens

Consider the multifamily market as an example. Today there is both a housing shortage – impacting the low and middle incomes – and an “amenity war” for new construction projects. This escalating amenity war is classic “sustaining” innovation, with developers escalating with basketball courts, automatic lighting systems and various other expensive (and underutilized) amenities.

Disruptive Innovation

We often equate term “disruptive” with “better”. But in Christensen’s’ model, that is imprecise, and in fact the “disruptor” is often inferior in many ways. Let’s consider two “innovations”: Sidewalk Labs and the rise of the self-storage industry.

Sidewalk Labs was created by Google to develop the “city of the future” in a neighborhood in Toronto. Sensors, timber, modular construction, new materials, super cool and innovative stuff. The self-storage industry arose over the past 30 years in cheap, ugly boxes as a convenient option for storing stuff. A classic low-end disruptor.

Disruptive products tend to be simpler, cheaper, more reliable and convenient than established products. In this framework, the creation of self-storage is a more innovative concept than Sidewalk Labs.

Christensen then distinguishes between two types of disruptive innovation:

· Low-end disruptions offer a product that already exists. This new product is typically cheaper (and in many ways inferior to the existing competitors). Southwest Airlines entered the industry with no frills and with limited flights, attacking incumbents from below.

· New-market disruptions appeal to a new need or desire. The transistor radio, invented in the 1950s, was a new-market disruption. Incumbents usually ignore this, because they can’t prove it.

Disruptive innovations, with their lower cost structures, ultimately pressure established companies. Christensen illustrates this with the steel industry’s mini-mills. These facilities, which melt scrap steel, are smaller than traditional integrated mills using blast furnaces. Emerging in the 1970s, mini-mills initially produced only low-quality rebar due to their simpler, cheaper process. Despite this limitation to the least valuable steel market, their cost advantage positioned them to challenge industry incumbents.

However, as the theory predicts, mini-mills rapidly improved their ability to make better steel and started to compete in markets that had more value. Eventually they destroyed the profitability of the integrated mills.

In these types of disruptions, entrepreneurs are ignorant of market demand, making traditional research impossible. Their plans must be to learn, ahead of implementation. As important pieces of information are discovered, project and business plans can evolve. This uncertainty is uncomfortable, especially for large firms with fixed processes.

Challenges of Creating Disruption Within a Large Firm

Executives at large successful firms are good at listening to existing customers, but bad at discovering new markets. This is not illogical, since most innovation is “sustaining”, making existing process and products better. Large firms are typically successful here, as they are making their existing customers happy and presumably doing what their investors expect. But the following three principles, all from Dilemma, are revealing:

1. Big companies need big markets

2. Markets that don’t exist can’t be analyzed

3. An organization’s capabilities define its disabilities

Large real estate firms – think Blackstone, Tishman, Hines, AvalonBay – need scale, require lots of proof, and have blind spots. Success binds people to certain pathways and process, blinding them to other opportunities. Dilemma’s research shows that firms move upward through time, seeking out higher quality customers and higher margins. Simultaneously they also acquire this cost structure, which makes it challenging to move back down market. Large firms are upwardly mobile, and downwardly immobile.

GM and Ford had been trying to introduce a successful electric car for years before Telsa, but they were doomed to fail because they were locked inside their own value networks, comparing expensive new technologies with their already well-refined products and process. In real estate, if a housing “product” is the solution to the housing crisis, it almost certainly needs to come from a new Tesla-like company that can face the problem with new eyes.

Christensen notes that for disruption to happen inside of a large firm, they must either buy it, create it from existing resources, or spin it out from the existing firm. Regardless of which is chosen, the size of the (new) team must match the size of the (new) opportunity.

How can real estate investors utilize this ’Innovators Dilemma’ framework? If you are an:

ENTREPRENEUR OR A SMALL, SCRAPPY COMPANY:

· Consider whether your innovation is sustaining an existing strong position, low-end disruption or new-market disruption. Then determine if that is appropriate for your current seat and the market opportunity.

· Set aside the ego. A key takeaway on this work, to me, is that “disruption” doesn’t need to mean fancy and expensive. And in fact, it probably shouldn’t.

· Entrepreneurs should seek out what can be offered at a cheaper, simpler approach. Where can you focus on smaller customers with lower needs?

o STUF takes existing vacant office space and utilizes for self-storage.

o Switchyards offers simple, affordable neighborhood workspace.

o Blank Street Coffee takes small spaces and doesn’t offer room for seating.

EXEC AT A LARGE PE REAL ESTATE FIRM:

· Passing over disruptive innovations is often rational for large firms. Your current customers and investors deserve your focus. Don’t feel bad.

· Watch out for overshooting the market, recognizing that it’s a business tendency that you might not otherwise recognize.

· If large firms do want to disrupt, they need to spin out, acquire, or create small teams that operate independently, and appropriately match the size of the market opportunity.

Leave a comment